Monstrous Wholesomeness: How To Be A Feminist “Art Monster” Poet and an Episcopal Priest

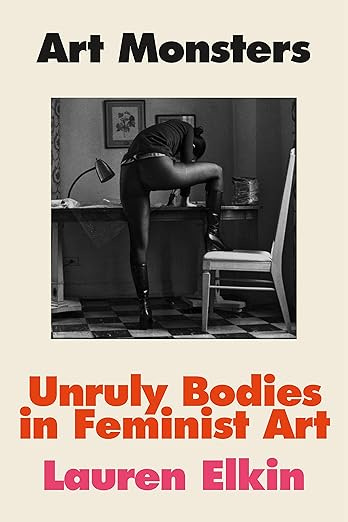

Reflecting on Lauren Elkin's Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art, Ordination Vows, and Biblical Women of Excess and Transgression

Recently I finished reading the fabulous book, Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art by Lauren Elkin, and have been contemplating its connections to how I view the relationship between creative work and my identity as a priest, especially given my upcoming MFA program. (If you somehow have ended up on this Substack but don’t follow me on any other social media, hi! I’m starting an MFA at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA in August and it’s a major life change!!!)

Some of you know that in Spring 2024, I took a sabbatical from church work (this is a regular offering for clergy in my denomination after five years of service in a particular parish). During that sabbatical, I picked up The Story of Art Without Men by Katy Hessel, which prompted a concentrated creative turn towards poems inspired by the visual arts. After finishing the book, I craved more information on women artists and began listening to Hessel’s podcast, Great Women Artists, and seeking other opportunities to learn about art.

During this immersion into the stories of creative women, I embarked on my application process for Master of Fine Arts programs in creative writing. These women of earlier eras often had more odds stacked against them than I’ve ever faced, yet they put their whole hearts into pursuing art anyway. Their trajectories as artists have made me hopeful about taking the risk to devote myself to further creative study.

Reading Art Monsters has built on this immersion, providing artistic education and food for thought on my own creative practice and identity. The title Art Monsters can refer to the monstrous being depicted within the art and/or artists themselves, who earn the label for their perceived transgressive or unfeminine qualities. Often, Elkin points out, monstrosity and transgression can be at the heart of what it means to create feminist work.

Lauren Elkin puts it this way: “I realized the word monster was just as effective as a verb: art monsters….it makes the familiar strange, wakes us from our habits, enables us to envision other ways of being, and lets the body and the imagination speak and dream outside the strict boundaries placed on them by society, patriarchy, internalized misogyny” (p.14). As the book continues, Elkin draws on artists, writers, and theorists who help illuminate the relationship between monstrosity and feminist thought. She quotes Hélène Cixous, for instance, who wrote, “If woman has always functioned [within] the discourse of man….it is time for her to dislocate this ‘within’, to explode it, turn it around, and size it; to make it hers, containing it, taking it in her own mouth, biting that tongue with her very own teeth to invent for herself a new language to get inside of” (p. 51). There is an urgency and a violence to the description here; it is not a tame thing to find one’s voice.

Art Monster conveys a need common to many creative women: having to actively working against their inclination towards self-censorship in order to fully blossom as artists, writers, etc. In order to fight self-censorship, many women writers and artists have had to push themselves into seemingly provocative territory. One example is Helen Chadwick, an artist who worked in the 1970s-1990s and inspired much flak from her fellow feminists by using her nude body in her work. Despite the criticism of her peers, Chadwick persisted. She said, “I was looking for a way of creating a vocabulary for desire where I was the subject, the object, and the author” (p. 262).

More recently, Kara Walker has created work that is controversial for its depictions of the violence of slavery and racism. Elkin quotes an interview of Walker, where Walker states, “If the work is reprehensible, that work is also me, coming from a reprehensible part of me. I’m not going to stop doing it because what else could I do?” (p. 110).

Example after example, I resonated with the artistic battle against self-censorship, necessary for the sake of finding language rooted in my own perspective and experience. In my own writing, I try not to indulge in the self-censorship that would inhibit me from creating the kind of work I want to make in the world. I believe Elkin, and many of these feminist artists, would argue that is a tough task for any woman, or anyone else marginalized in our society by virtue of some of their aspect of their identity. My context has one admittedly rare complication; I also have to figure out what self-censorship looks like as an ordained woman, an Episcopal priest, who has taken on, by choice, a certain spiritual and professional role.

Elkin writes, “The first person…has often been denied women and other marginalized people unless it confirms to what they – they, the patriarchy, the tastemakers, the one who decide things - expect to hear from us. And then it’s rejected or minimized for being small, anecdotal, irrelevant to the Big Concerns like politics, war, business, sport. Particular instead of universal. We get accused of being narcissistic, inappropriate. We say too much; we overshare. (The persistence of feelings!)” (p. 28). I cannot think about creative concerns about inappropriateness, oversharing, and narcissism without thinking about my role as a priest.

After all, among the ordination vows, every Episcoal priest is asked, “Will you do your best to pattern your life in accordance with the teachings of Christ, so that you may be a wholesome example to your people?” Wholesome strikes me such as a weighty word – and to some degree, an unclear one. Despite its vagueness, it certainly its connotations lean more Hallmark or Disney Channel Original Movie than they do feminist art. “Wholesome” is, I’ll admit, not among the first words I associate with Jesus Christ, who the Gospels show to be both a man of tradition and a provocateur, constantly challenging the people around him. On the day I first began drafting these thoughts, the Gospel passage that my church heard that morning included Jesus telling people to abandon burying their dead in order to follow him. I’m not sure that would’ve sounded so “wholesome” to the families of those first disciples.

As I thought about my relationship to priesthood and my own draw towards being an “art monster,” I began thinking about women in Scripture who might, in one way or another, be construed as monstrous, excessive, or transgressive. On one hand, there are the women who show up in Scripture as villains, villainous metaphors, or both: Jezebel (1 Kings), Gomer who gets called a “wife of whoredom” (Hosea 1:2), the “foolish woman” of Proverbs, or the whore of Babylon (Revelation). To figure out my relationship to those women would be another worthy essay, but at the moment, I am more drawn to those who the biblical texts hold up as exemplars who also might be regarded as monstrous, excessive, or transgressive.

The example that feels most obvious to me is the woman who washes Jesus’s feet with her hair. One of my favorite biblical resources, the Jewish Annotated New Testament, notes this about her actions: “an intimate and hardly common practice. Loosened hair indicated grief, gratefulness, propitiation of a god, or pleading, and need not be taken as erotic.” Although scholarship suggests we don’t need to interpret her act as erotic, it is unabashedly, unavoidably embodied. The criticism recorded is, “If this man were a prophet, he would have known who and what kind of woman this is who is touching him, that she is a sinner” (Luke 7:39 NRSV). The touch itself is part of what is considered inappropriate. Jesus, however, sees her differently: “she has shown great love” (Luke 7:47 NRSV).

Another woman who could’ve easily been painted as monstrous was Rahab, a Canaanite sex worker in the book of Judges, yet she is portrayed as a biblical hero. Her heroism, from the perspective of the biblical writers, has to do with aligning herself with the Israelites and their God, but from my perspective as a contemporary reader, I laud Rahab’s quick thinking, her ability to save herself and those she loves in the midst of great potential violence. We might also throw Ruth into the mix, who has a a seemingly excessive devotion to mother-in-law (so much so that her words to Naomi are often used in weddings!) and pursues a potential husband with clear forwardness and impropriety, or Tamar, a widow in Genesis who poses as a sex worker in order to have sex with, and conceive a child by, her father-in-law after suspecting she was being shut out of the family line. From the New Testament, we might also include the woman at the well of John 4, who had five past husbands (we don’t know the backstory there) and now has a man who isn’t her husband (again, no backstory). Jesus speaks the truth of her relationships past and present without condemnation (though people tend to assume there’s condemnation that is going unsaid), and she goes on to be a powerful witness to his identity, with many Christians naming her “the first evangelist.”

All of these women could easily have been portrayed as monsters, since they shamelessly expressed themselves or went after something they wanted. Yet here they are in Scripture, celebrated as examples of faith and righteousness. When I think, then, about what it means to be a “wholesome example” “in accordance with the teachings of Christ” in light of these women – maybe wholesomeness doesn’t have to be in contradiction with what Lauren Elkin describes as monstrosity. Maybe wholesomeness has more to do with wholeness than narrowness.

If I take the Dictionary.com definition, “conducive to moral or general well-being; salutary; beneficial,” to heart — well, isn’t it conducive to general well-being – isn’t it beneficial – to “envision other ways of being, and let…the body and the imagination speak and dream outside the strict boundaries placed on them by society, patriarchy, internalized misogyny”? Isn’t it beneficial for a woman to “invent for herself a new language”? Wholesomeness may sometimes require us to step outside the restrictions that others would place us for the sake of our own health – for the sake of our souls! Wholesomeness may require embracing our bodies and words in self-expression in ways that others would deem “inappropriate.”

To be very clear, I still believe boundaries are very important for clergy, particularly within pastoral relationships (the relationships that a priest cultivates in their spiritual care, particularly in the community that they serve). Context matters. The “monstrous wholesomeness” that I can explore in a poem may not be the right fit for a pulpit or for conversation with people in my parish. While clergy are full human beings, we also play particular roles in the lives of the people who entrust us to prayerfully accompany and encourage them through the ups and downs of life. In the context of being a parish priest, my “monstrous wholesomeness” might look like what others would consider an “excessive” commitment to feminine language for the Divine; a refusal as a young-ish clergywoman to try to conform my style of clergy dress to standards of another generation or gender; or bringing up trans rights and reproductive rights from the pulpit. But in the realm of my poetry, I feel I must allow my “monstrous wholesomeness” to go even further into the “monstrous” – not in opposition to the values of my priesthood, but as a way of fulfilling them in a different space and from different angle.

As a poet-priest who is committed to a feminist creative practice, I must confront the tendency towards self-censorship that is formed from the overlapping realities of my womanhood and the spiritual (and institutional!) calling I hold within the complex tradition that is Christianity. Even in a denomination that has room for “progressive” theology, for lack of a better term; that is often LGBTQ+ affirming; and that includes women in leadership, there are still things I may feel called to lift up through my poetry that might be uncomfortable to other clergy (even other clergy creatives) or Episcopalian more generally. The Episcopal church (along with many other denominations that have made important progress in terms of gender equality and affirming LGBTQ+ identities/experiences and rights) still has an inherited discomfort with bodies and desire – with those things feminist artists contended with decades ago, and that feminist artists must still contend with now. In my poetry, I have an outlet to perhaps push at those places where I think the church still might have room grow, or to converse with those places where I am not seeing myself, or my values, in our public theology or conversation.

In the end, this is not really an essay on how to be an “art monster” poet and priest (if there is a “how,” I am guessing it is in the poems itself, especially the ones that are scariest to publish), but more of an admission that I expect to be doing ongoing processing (maybe for my whole life?) about how these things go together….and maybe, at times, how they don’t! As I head into my MFA, a next chapter where poetry will get to take center stage even though I will continue to also serve as a priest, “wholesome art monstrosity” feels like a mission statement of sorts! I am excited and nervous to get to better know the “art monster” within during the years ahead, and I hope you’ll journey with me as I share what she produces.

Poetry news:

I have had two poems come out recently. I’d love if you’d give them a read and, if you enjoy them, share them with others!

“Even the Trees Get to Be Slutty” – Broadkill Review

Earlier I wrote about my sabbatical, and this was a sabbatical poem, drafted in a nature writing workshop at Calvin University’s Festival for Faith & Writing. This feels very appropriate to share given these musings on self-censorship. During the workshop, we were asked to share what we’d written so far, and I had to look around the room of mostly Christians I had just met and wonder if I could even read the poem! Admittedly, I did self-censor – skipping the title – but was stubborn enough to share the rest of the poem. Thank you, Broadkill Review, for giving this poem a home!

“Once, Offhandedly, An Ex-Boyfriend Said He Hoped I Could Find Someone Who’d Be OK With Me Working on Sundays” - Moist Poetry Journal

As I mentioned, I’ve been doing lots of poems lately based on visual art, especially by women artists; this poem brings together contemporary experience/feeling with an 18th century self-portrait by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard. This is one of many poems indebted to Katy Hessel’s work in The Story of Art Without Men. It is always a pleasure to be published in Moist! This is my third poem published there from over the years.

I recently had a great reading at Christ Church Cathedral in Springfield, Mass. and am so thankful for all who joined me there! I suspect this was my last New England reading for a little bit, but I’ll be excited to begin sharing about readings in the Virginia area once I get settled in.

As always, my collections remain available. If you haven’t bought my chapbook Woman as Communion yet and want a way to support me as I head towards the MFA (both monetarily and in helping me reduce my book haul I have to move with a little bit!), I can sell you a signed copy directly for $15! Please reach out to me here or at contact@meganmcdermottpoet.com. It is also available for purchase from Game Over Books and other online retailers.

Jesus Merch: A Catalog in Poems and Prayer Book for Contemporary Dating (a physical copy or online for free!) are also still available for your reading pleasure! If you’ve read and enjoyed any of these collections, please consider leaving a review on Amazon, Storygraph, Goodreads, social media, etc.

Substack news:

I’ve still been thinking about moving platforms but am having trouble with the tech side of things! For anyone who has jumped the Substack ship, tell me your thoughts on what’s working for you, and if you could be so kind, how to easily move subscribers to your recommended platform!